It’s been established that the pivotal moment in the evolution of the human diet was the addition of meat and bones from large animals to the menu, dating back to at least 2.6 million years ago. This dietary shift was a game-changer for our ancestors and marked the beginning of a new era in human evolution. It was the start of the proper human diet.

An Omnivorous Diet

Early hominins were likely omnivorous, much like modern chimpanzees, consuming a diverse range of foods, including fruit, leaves, flowers, bark, insects, and meat. Studies of tooth morphology and dental microwear indicate that some hominins may have also consumed tough food items such as seeds, nuts, and underground storage organs like roots and tubers.

The Shift to Meat-Eating

However, by 2.6 million years ago, the diet of some hominins underwent a radical transformation as they began incorporating meat and marrow from small to large animals into their meals. But what led to this dietary shift? Let’s delve into the evidence using the 5 Ws: When, Where, Who, What, Why (and How).

The Dawn of Hominin Carnivory

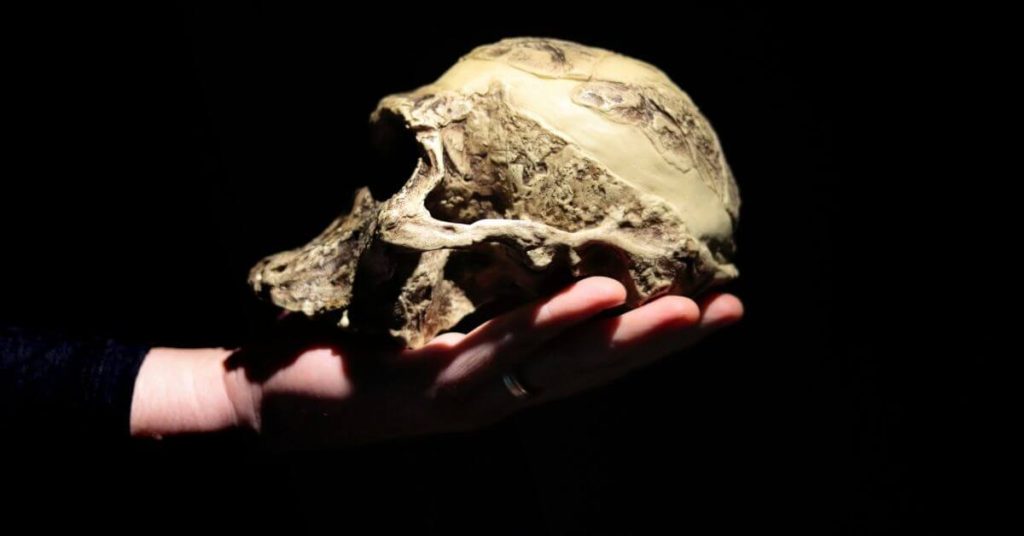

The earliest evidence of hominin carnivory can be traced to the discovery of butchery marks on fossils. Cut marks, which are a result of slicing meat off the bone with a sharp-edged tool, and percussion marks, which are produced by breaking open bones to extract the marrow inside, are collectively referred to as butchery marks. These marks are crucial in determining the extent to which hominins relied on meat as a source of food.

The Uncovering of Butchery Marks

The significance of butchery marks was first recognized by scientists in the 1980s when they began to find evidence of these marks on Early Stone Age fossil assemblages. The study of butchery marks has since evolved, with researchers exploring not just the evidence of meat eating but also the role of bones in the hominin diet. In recent years, there has been a growing body of experimental and prehistoric evidence for humans chewing on bones.

In conclusion, the discovery of butchery marks on fossils is the strongest evidence of hominin carnivory, offering insight into the dietary habits of our ancestors. The continued exploration and understanding of these marks are vital in piecing together the evolutionary history of the human diet.

A novel dietary behavior, the consumption of animal flesh by hominins, can be traced back to at least 2.6 million years ago. This conclusion is drawn from the presence of butchery marks on fossilized bones found at the Gona site in Ethiopia, which marks the earliest well-accepted evidence for this transformative shift in hominin behavior (Blumenschine & Pobiner, 2006).

Interestingly, this also coincides with the emergence of archaeologically visible accumulations of stone tools (Semaw et al., 2003). The discovery of butchered bones at the Dikika site in Ethiopia, potentially dating back to 3.4 million years ago, has also been made. However, the evidence consists of only a few specimens and is still disputed (Domínguez-Rodrigo et al., 2010).

The first well-documented instance of persistent hominin carnivory, with fossil fauna found in association with large concentrations of stone tools, comes from the Kanjera site in Kenya around 2 million years ago (Ferraro et al., 2013). Additionally, by 1.95 million years ago, hominins had begun to incorporate aquatic foods like turtles, crocodiles, and fish into their diets, as evidenced by the Koobi Fora site (Braun et al., 2010).

The Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, dating back to 1.8 million years ago, offers multiple localities with in situ butchered mammal remains ranging from hedgehogs to elephants and associated with significant numbers of stone tools (Domínguez-Rodrigo et al., 2007; Blumenschine & Pobiner, 2006). However, at three Koobi Fora sites in Kenya from around 1.5 million years ago, butchered mammal remains were found, but without the presence of stone tools (Pobiner et al., 2008). This may signal a shift towards intentional specialization of activities across the landscape, such as animal butchery and stone toolmaking being conducted in different areas.

However, the exact nature of this shift remains uncertain, as the scarcity of archaeological evidence from this time period makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Despite this, the evidence of butchered animal remains and the presence of stone tools at multiple sites provides a clear indication that hominins were incorporating meat into their diets by at least 2 million years ago.

This dietary shift is considered a major turning point in hominin evolution, as it would have provided a reliable source of protein, allowing for the evolution of larger brains and the development of early human societies. It is believed that the ability to effectively process and consume animal flesh played a crucial role in the survival and success of our early human ancestors.

However, the story of early human carnivory is still far from complete. Further research and discoveries at new sites have the potential to shed light on the origins and evolution of this critical aspect of human behavior. As our understanding of the past continues to grow, we are able to piece together a clearer picture of the fascinating and complex journey of human evolution.

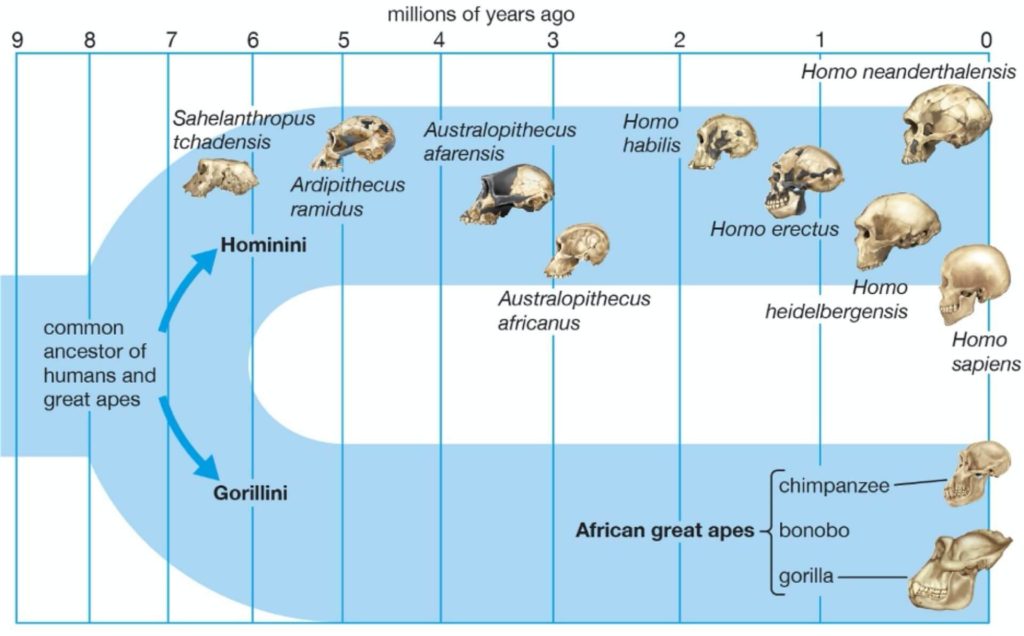

The mystery of who was feasting on the meat and marrow of prehistoric animals has long been a subject of intrigue. Recent discoveries in the fossil record have shed some light on the possible culprits. At around 2.6-2.5 million years ago, at least three species of hominins were present: Australopithecus africanus, Australopithecus garhi, and Paranthropus aethiopicus.

The earliest of these species, H. habilis, is believed to have existed by 2.4-2.3 Ma. However, while butchered bones have been found near the fossils of A. garhi, it is within the Homo lineage – specifically Homo erectus – that we see the tell-tale signs of a meat-eating lifestyle, such as a reduction in tooth and gut size and an increase in body and brain size.

Unfortunately, no such evidence has been found in association with either A. africanus or P. aethiopicus, making it less likely that these species were responsible for consuming the meat and marrow.

So, the question remains: who was indulging in the juicy, nutritious flesh and rich, fatty bones of ancient animals? The answer may lie in the biological adaptations of Homo erectus. This species is characterized by its decreased tooth and gut size, as well as its increased body and brain size, which are all adaptations often linked to a diet rich in meat.

Additionally, butchered bones have been found near fossils of A. garhi, suggesting that meat-eating was not limited to the Homo lineage.

While the exact culprit may never be known, the evidence points to Homo erectus as the most likely candidate for the meat-eating hominin.

As our understanding of the fossil record continues to evolve, it will be fascinating to see what new discoveries are made and what they reveal about our ancient ancestors and their diets. Until then, the mystery of who was eating this meat and marrow will continue to captivate the minds of researchers and enthusiasts alike.

What Sets the Carnivory of Hominins Apart?

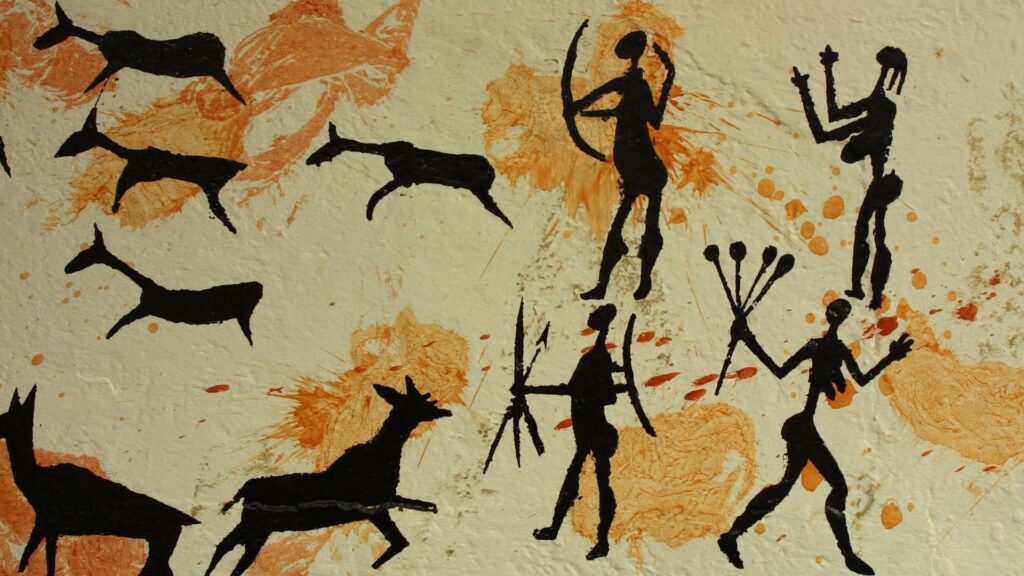

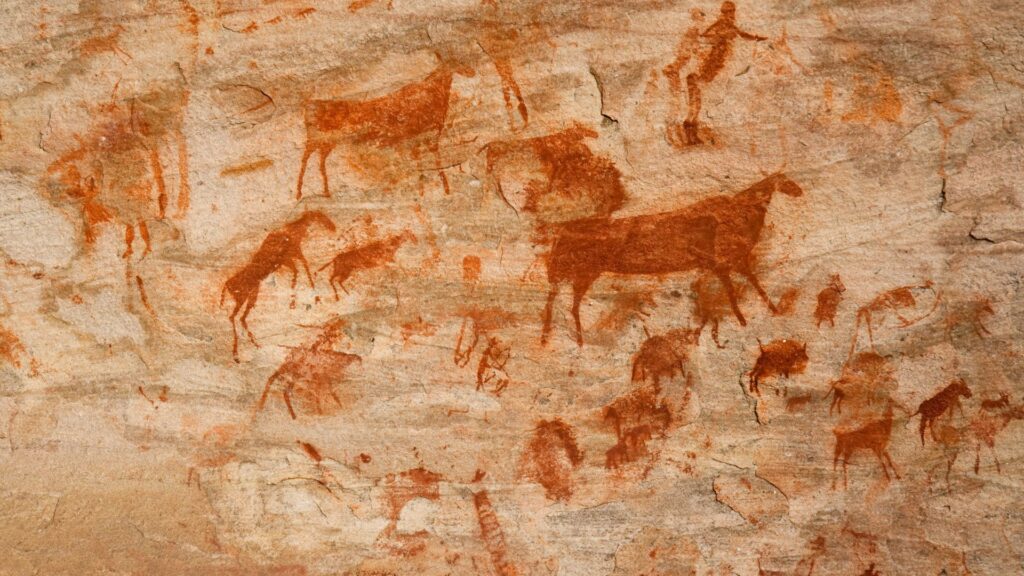

The distinctiveness of hominins’ carnivory among primates is embodied in three unparalleled traits: (1) utilization of flaked stone tools to secure meaty sustenance; (2) acquisition of prey much larger than their own physical size (Figure 3); and (3) scavenging of animal resources.

While chimpanzees, our closest genetic cousins, occasionally hunt and consume small monkeys like colobus, meat is a minimal component of their diet, and they almost never scavenge (Watts, 2008).

The reason for this could be attributed to their limited ability to digest carrion (Ragir et al., 2000). The origins of hominins’ discovery of this novel food source, however, remain a mystery.

As the African habitats expanded with the growth of grasslands, hominins would have faced difficulties in exploiting grass directly (Sponheimer et al., 2013). Nonetheless, an increase in large herbivores would have been a beneficial resource for any species that could both obtain and process them (Plummer, 2004).

This marks a decisive shift for primates, as they encroached on the carnivore guild, which presented them with new selective pressures (Brantingham, 1999; Pobiner & Blumenschine, 2003; Werdelin & Lewis, 2005).

The use of flaked stone tools to access animal resources enabled hominins to overcome the physical limitations that prevented their ancestors from exploiting this food source.

This technological innovation not only opened up new dietary opportunities but also had profound implications for hominin evolution. The ability to process animal tissue with stone tools would have provided hominins with a source of high-quality protein essential for brain growth and development (Leonard & Robertson, 1992).

The acquisition of resources from much larger animals was also a unique achievement. It required advanced hunting skills, cooperative behavior, and social organization.

The procurement of large animal resources would have had a significant impact on the hominin diet and would have increased the diversity of nutrients available.

This dietary shift was likely accompanied by a significant increase in caloric intake, which would have allowed for more energy to be devoted to other aspects of life, such as reproduction and toolmaking (Bunn & Ezzo, 1993).

Scavenging as a food acquisition strategy was another remarkable aspect of hominin carnivory. Unlike chimpanzees, hominins scavenged animal remains, providing them with a reliable source of food even when hunting was unsuccessful.

The ability to scavenge would have been especially important during times of food scarcity, such as during droughts or when animal populations declined (Blumenschine & Peters, 1995).

The carnivory of hominins was unique among primates, shaped by their ability to access animal resources through flaked stone tools, hunt large animals, and scavenge for food. This dietary strategy had a profound impact on hominin evolution and opened up new opportunities for growth and development.

The question of why hominins started consuming more meat and marrow remains shrouded in mystery. However, the reasons behind this shift in diet are gradually being uncovered through research and analysis. Meat and marrow were attractive food sources due to their calorie-dense nature and provision of essential amino acids and micronutrients.

This, coupled with the fact that aquatic fauna, was a rich source of nutrients needed for brain growth, made these food sources ideal for hominins. The consumption of animal foods allowed hominins to increase their body size without sacrificing mobility, agility, or sociality.

However, the extent to which hominins relied on animal tissues versus other foods remains unclear. The frequency and quantity of nutrients obtained from animal tissues are difficult to determine.

Sites like FLK 22 and FLKN 1-2 at Olduvai Gorge have provided some clues by showing that hominins broke the long bones of small to medium-large mammals in direct proportion to their estimated caloric yield from marrow fat. Furthermore, the abundance of medium-large mammal bones at FLK 22 was positively correlated with the net yield of marrow bones.

The application of optimal foraging theory suggests that hominins consumed animal foods whenever they encountered them. The frequency of carcass encounters was influenced by various ecological variables.

This indicates that by 1.8 million years ago, hominins were making informed decisions about what to eat based on the energy yield of different food items.

The net yields from animal tissues were often comparable to, or higher than, non-mammal food items harvested by tropical hunter-gatherers.

In conclusion, the shift towards a diet rich in meat and marrow was motivated by the calorie-dense and nutrient-rich nature of these food sources.

The use of optimal foraging theory suggests that hominins made informed decisions about what to eat based on the energy yield of different food items. The consumption of animal foods allowed hominins to increase their body size without sacrificing mobility, agility, or sociality.

Why did hominins start eating more meat and marrow?

The benefits of consuming meat and marrow did not come without challenges, however. Hominins had to adapt to new environments, tools, and hunting techniques in order to secure these food sources.

They also had to overcome competition from other predators, who were also seeking to exploit the same resources. In addition, the acquisition and processing of animal tissues required significant investment in terms of energy and time.

Despite these challenges, the consumption of meat and marrow played a critical role in the evolution of hominins. The increased availability of calorie-dense and nutrient-rich foods allowed hominins to develop larger brains and more complex social structures.

This, in turn, enabled them to tackle new challenges and explore new territories. Over time, this led to the evolution of Homo erectus and, eventually, Homo sapiens.

The consumption of meat and marrow was a pivotal event in the evolution of hominins. While it brought significant benefits in terms of increased calorie intake and access to essential nutrients, it also came with challenges and required significant adaptation and investment.

Nevertheless, this shift in diet played a critical role in the development of larger brains, more complex social structures, and, eventually, the evolution of Homo sapiens.

How did early humans get and use this meat and marrow?

Hunting for sustenance has been a vital aspect of human survival since the dawn of time. The use of hafted spear points for hunting technology dates back to around 500,000 years ago, with the advent of complex projectile weapons appearing much later, 71,000 years ago.

The theory of persistence hunting as a mode of hunting without advanced technology remains a possibility, but without clear evidence in the fossil or archaeological record, it’s difficult to say for sure.

Fire, controlled and utilized at hearths for cooking, dates back to an astonishing 790,000 years ago, evidenced by burned seeds, wood, and flint.

While early indications of a fire in Africa, associated with hominins, are primarily seen through sediment discoloration, they are not widely accepted.

The anatomy and physiology of modern humans, with unique gut proportions and size compared to other great apes, along with genetic signatures of selection in genes related to dietary changes, suggest a key role in the adaptation to eating meat and marrow. However, the exact timeline of these transformations remains unclear.

The acquisition and utilization of meat and marrow by early humans was a crucial step in human evolution. It provided a new source of protein and fat, which helped to fuel the development of the human brain.

The discovery and mastery of hunting technology and the controlled use of fire opened up a new world of possibilities for early humans, allowing them to explore new habitats and diversify their diets.

This shift in diet and subsistence strategy likely had a profound impact on the social, cultural, and technological development of early humans.

The evidence for early human hunting and the controlled use of fire shows just how resourceful and innovative our ancestors were. Despite facing a challenging and constantly changing environment, they were able to adapt and thrive.

The study of early human hunting and subsistence strategies offers valuable insights into the evolution of human behavior and the development of early human societies.

In conclusion, the acquisition and utilization of meat and marrow by early humans was a critical turning point in human history.

It allowed our ancestors to expand their dietary options and overcome the limitations of a solely plant-based diet.

The evidence of early human hunting technology and the controlled use of fire serves as a testament to the resourcefulness and adaptability of early humans and highlights the important role that food and subsistence played in shaping human evolution.

The topic of whether early hominins obtained animal carcasses through hunting or scavenging has been the source of much debate among zoo archaeologists studying Early Stone Age faunal assemblages.

Despite the abundance of butchery marks found on fossils, interpretations of the evidence have been swayed by implicit biases that view hunting as a more advanced and modern behavior than scavenging.

The debate has been fueled by numerous studies, ranging from analyses of the FLK 22 Zinjanthropus site at Olduvai Gorge to actualistic studies of resource availability from scavenged carcasses.

Although the issue of hunting versus scavenging has been extensively studied, it remains unclear which of these two procurement methods early hominins primarily relied upon.

Instead, it is believed that the hominins employed both hunting and scavenging depending on a variety of behavioral and ecological factors.

Experiments aimed at determining the frequency and location of cut, percussion and tooth marks on fossils have provided insight into the timing of access to the animal carcasses and the identity of the accumulator or accumulators.

These studies have been critical in informing our understanding of early hominin behavior, but it is unlikely that a definitive answer to the hunting or scavenging debate will ever be reached.

In conclusion, the acquisition of animal carcasses by early hominins was likely a complex and dynamic process that depended on a variety of ecological and behavioral factors. Further research is needed to fully understand the nature of these relationships and how they have changed over time.

It’s clear that the procurement of animal resources was a critical component of survival for early hominins, and the hunting versus scavenging debate is a reflection of the ongoing effort to better understand their behavior and lifestyle.

Regardless of the predominant procurement method, the ability to access and utilize animal resources was a major factor in the evolution of early hominins.

These early humans had to adapt to changing environmental conditions, including fluctuations in food availability and the presence of other predators. Their ability to effectively obtain animal resources, whether through hunting or scavenging, was likely a key factor in their survival and success.

In addition, the study of early hominin procurement strategies also sheds light on the evolution of human cognition and social organization.

Hunting and scavenging would have required different skills, knowledge, and social relationships, and the ability to effectively employ these procurement strategies would have played a role in the development of early human cognition and social structure.

In conclusion, the study of early hominin procurement strategies is an important area of research that provides insight into human evolution and behavior.

Whether hunting or scavenging was the predominant procurement method remains an open question, but it is clear that the ability to effectively obtain animal resources was a critical component of early hominin survival and success.

Order Lies My Doctor Told Me today, as your first step towards a better diet, better health, and a better relationship with your doctor.

This post contains affiliate links, and as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases that help keep this content free. (Full disclosure).